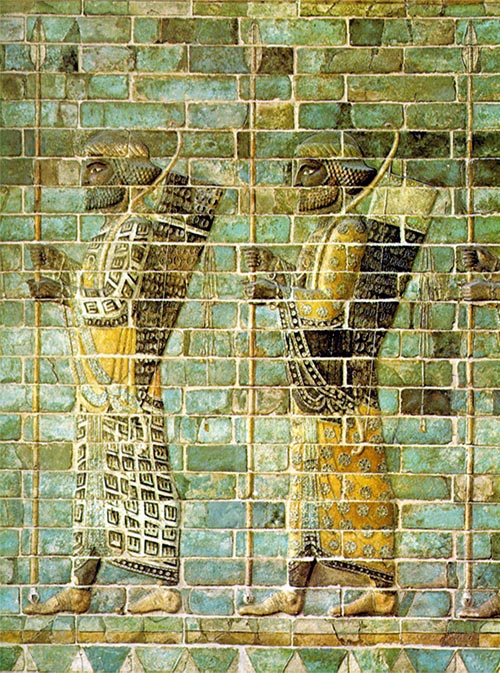

In the film 300, 2007 by Zack Snyder, audiences follow the story of a battle between the Spartans and Perisans. The Spartan’s are led by King Leonidas who faces off against King Xerxes and the Persians. According to an article by Dean Richards in the Chicago Tribune titled Film gives stars ‘rippling abs’ , 2007 it suggests that most of the film was made through use of CGI. In this article Richards interviews the cast as well as director Zack Snyder. The director Zack Snyder tells Richards that 300, 2007 had a “small budget of $60 million; 1.306 digital effects were used in the film” (Snyder, 2007). This is quite an amazing feat considering most ancient roman films have been shot naturally without the use of CGI. In the past, films like Quo Vadis, 1951 built enormous sets and had extremely large budgets. As modern technology has advanced film producers have been able to rely on shooting scenes with green screens inside a studio more and more, saving money on elaborate film sets and extras. One of the most interesting parts about the making of the film 300, 2007 is that it is highly based on the comic book also titled 300, 1998 by Frank Miller. In the short film 300 | A Glimpse from the Set: Making 300 the Movie | Warner Bros. Entertainment, 2020 director Zack Snyder discusses how all of the elements of the comic book were almost identically replicated in the adaptation to the big screen.

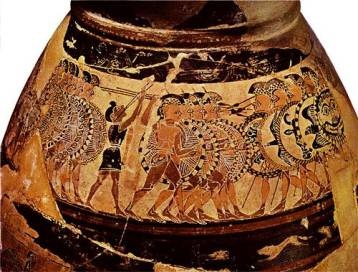

In the short film Snyder goes into detail about some of the aspects of how CGI can create these landscapes that would not be possible if you were shooting with a regular camera. Snyder makes a very interesting point when discussing the first battle scene where the Persians descend on the Spartans near the water. He explains that “when you blow out a highlight in a photograph the sky would be white. That’s not what happens in 300. The highlights are blown out but the sky still has detail and in some ways even though it sounds super simple, it’s incredibly different from the way you see” (Snyder, 2020). This is a fascinating point by Snyder as it suggests that many of the important scenes from the comic book would not have been able to be recreated without the use of CGI technology. The film 300, 2007 uses CGI to make the battle scenes look extremely dramatic and brutal like they once were back in ancient times. In Ancient Rome and Greek history there have been many examples of the brutality of battle, but none better than the Iliad. The Iliad is an ancient epic poem which was written by Homer. The Iliad and the film 300 have many similarities in their depictions of combat. In Book IV of the Iliad there is a section that is very similar to the scene in 300, 2007 at the 52:03 minute mark of the film. This section of the Iliad states “He struck at the projecting part of his helmet and drove the spear into his brow; the point of bronze pierced the bone, and darkness veiled his eyes” (Homer, Book IV). Here, there is brutal murder that occurs as a spear has gone through a warrior’s head. This section is almost uncanny to the 52:03 mark of the film 300, 2007 where a Spartan kills a persian by throwing a spear through their head. The CGI in the film 300, 2007 is an amazing feat and it enhances the viewing experience immensely. Although the film 300, 2007 is not an entirely non-fictional tale, it does an impressive job of emulating 300, 1998 the comic book as well as ancient texts such as the Iliad.

Homer. “Book IV” Iliad

Zach Snyder. 300 (2007)

Mervyn Leroy. Quo Vadis (1958)

300 | A Glimpse from the Set: Making 300 the Movie | Warner Bros. Entertainment. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v–r6XKICks&t=4s

Miller, Frank. 300. Dark Horse Books, 1998.

Richards, Dean. “Film Gives Stars ‘Rippling Abs’.” Chicagotribune.com, 24 Aug. 2018, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2007-03-09-0703100025-story.html.